It soon became obvious that if the art of painting was to continue, figuration would have to be re-introduced in a new and thoroughly modern way. But who were the older practising artists to whom we could aspire? I had seen and liked the work of Richard Diebenkorn and Philip Guston’s new paintings from the late sixties. In Britain we had former abstract artists like Roger Hilton and Keith Vaughan who were exploring a new kind of figuration which gave some encouragement. Another figure, somewhat away from the mainstream was the Australian, Sidney Nolan, a clever and intuitive artist. Of the painterly developments in Europe at that time including Germany we knew almost nothing. Desperate for something visually interesting and exciting to look at it was inevitable that I looked back to the art of the early Modernists as I felt myself stuck in a cheerless and dreary contemporary environment,

Surrealism and then German Expressionism ( especially the works of Kirchner in the period just before the Great War) were my first interests, as they seem to be for many young art students. I spent hours looking at the works of Braque, Leger and especially Max Ernst, liked Klee and Mondrian and for some reason which now escapes me the Swiss artist Hans Arp. Post-impressionism especially Gaugin who I was once quite keen on was about as far back as I looked at that time. I know its a terrible thing to say but I have always thought of Cezanne’s close toned paintings which in many ways are so admirable as depressingly dull and though I find much of Van Gogh lovable I like his work less as it becomes more characteristically swirly! I respected rather than liked Picasso, thought most of Miro and Chagall lightweight, Kandinsky pretty hopeless and was never much impressed by the hugely influential Marcel Duchamp. I saw Pollock and some of the other abstract expressionists as pretty much the last group of artists worth aspiring to. Even at that time Matisse occupied a pre-eminent position and it seemed to me that his work, especially the austere paintings from around the time of the First World War were years ahead of anything being done currently. My opinion of modern British painting was not high; Bacon was there of course, but there seemed nothing to be got from him, and the same went for went for Ben Nicholson. Auerbach and Freud were active but I discounted their work as hopelessly backward-looking; I still today have misgivings about their painting, though I now see it as an unappealing example of MAN art- the sort of stuff produced by people who want to be taken seriously and above all respected, and while some of their works especially Freud are pretty good they come nowhere close to Soutine when hot. I had quite a high regard for some of the poetic landscapes of Paul Nash, but one kept quiet about that sort of thing in those days!

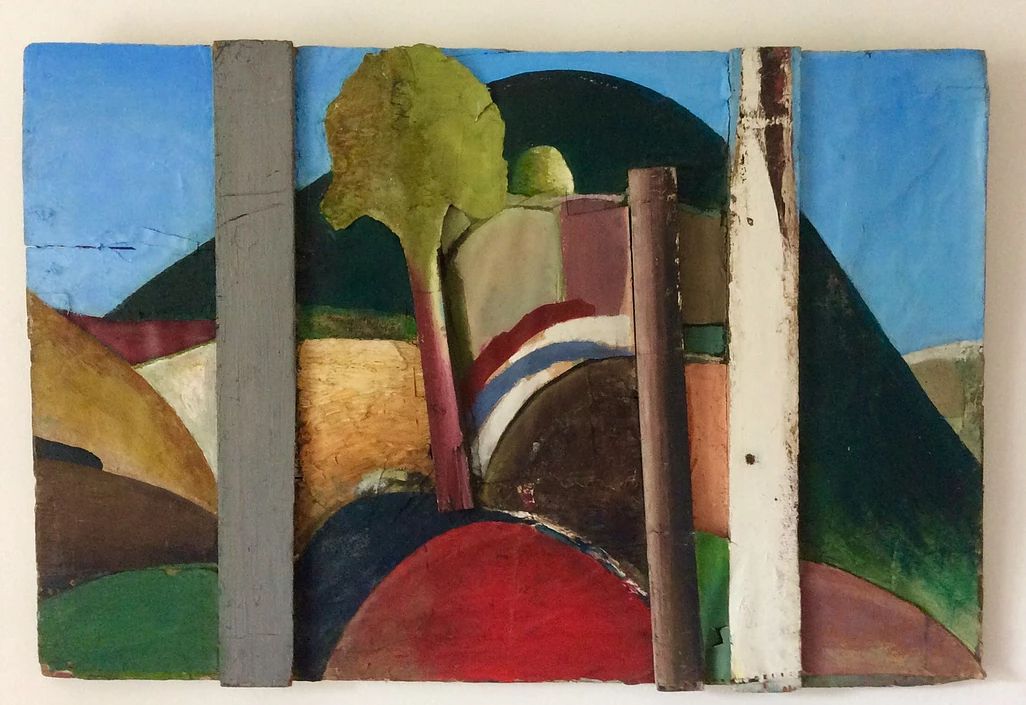

It was in the Autumn of 1972 after a two year foundation course in Essex, that I started at Bath Academy of Art, then situated at Corsham, Wiltshire. During my first term there with Adrian Heath as my tutor, I produced a series of collages, many of which were abstract but most relating to the English landscape. The series ended with Wiltshire Landscape December 1972, a position from which I found it hard to advance. After this high point I more or less abandoned collage and assemblage and went back and tried to develop an entirely painterly style.

One day in early 1973 a fellow student, David Jones, whilst discussing the above painting, suggested that I look at the work of Howard Hodgkin who had taught at Corsham a few years before, lived nearby and was a close friend of our esteemed painting tutor Peter Kinley. With the typical arrogance of youth I dismissed his advice. However in the influential exhibition “British Painting 1974” at the Hayward Gallery, I was very impressed by his two paintings, which even today I consider among his very best work. Almost uniquely for that time he was producing thoroughly modern abstract paintings without ignoring the European tradition, and dare I say it, produced works which could be understood within the traditional ideas of beauty. One other student at college, Louisa Hutchinson, was similarly impressed and shortly afterwards I saw and admired her work in which she was exploring in her own way the creation of space through flat planes of colour as had Hodgkin.

On Saturdays many of us took the short bus ride into Bath. My own shopping was confined to hunting for novels in bookshops and LPs in the music shop of Duck, Son, and Pinker situated by Pulteney Bridge. Sunday was often my day for walking out. Corsham is situated on the south eastern slopes of the Cotswolds where they shelve down towards the Avon Valley and afford local walks of wonderful variety. Sometimes on longer warmer days I would take a packed lunch and go further afield, northward through Biddestone and Castle Combe toward the dry uplands and the remote wooded valleys of that part. Or my favourite way was to go southeast by Lacock making for those outliers of the Marlborough Downs at Roundway Hill above Devizes and the ancient heights beyond Calne and Cherhill.

It became a sort of mental habit on these long cross-country tramps to fall into a reverie of speculation about creating a massive all-encompassing work of art. First of all this work would need to be large in scale and glorious in colour. It would be structurally complex, intuitive in conception, full to overflowing with imagery coming directly from the subconscious yet mathematical in precision, while the subject matter would be dealt with in a way comical and paradoxical . The final image in my mind of how this would look constantly shifted, all these years later I remember it as maybe resembling the assemblages of Robert Rauschenberg but with more of beauty (not difficult)! Whatever it was, this youthfully ambitious, grandiose concept would have been totally at odds with just about everything that was happening in the Art scene at that time.

It wasn’t until 1979 after three difficult years in London that with Louisa Hutchinson I moved into a warehouse studio in Wapping and started painting again. We had looked at a lot of Renaissance painting in the intervening years which probably had an inhibiting effect on both of our work, at least in the short term. An entire year of hard work produced only one really successful result, “Still life with Torso, Parrot and Mirror.” Despite stubborn efforts the projected series of similar works failed utterly, my hopes probably finished off by seeing in the Louvre Georges de la Tour’s wonderful “Le Tricheur” 1638 and realising the impossibility and absurdity of continuing this line of development.

This impasse was ended when Louisa who was every bit as frustrated and lacking confidence as I was, said “let’s just break it and paint wildly with no subject at all”. She proceeded to paint in a short time a few powerful and dynamic paintings. Although I can’t say I liked them very much, they were certainly a breakthrough, looked fun to do and anything had to be better than being blocked, so I decided to have a shot at it. Meanwhile there was a return to painting; the Whitechapel Gallery, which was local to us, had a series of very important shows starting in 1980 with the Max Beckman triptychs and then in the following years shows of Baselitz, Lupertz, Brice Marden, Gilbert and George, Anselm Kiefer, Philip Guston, Clemente and Schnabel, interesting exhibitions which would have been unthinkable in the decade before.

We felt that after being isolated from the mainstream for so long we were now moving more with it, and that at last creative and exciting possibilities in painting were beginning to open up.

Now came a period of working out the new way of painting on a much larger scale and one without the stylistic constraints of the earlier work. If the old way was to shape form to make an image we might describe the new things as depicting the flow of a constantly changing dynamic universe, what I prefer to call the ‘Oceanic Sense’. This seeming dichotomy may be described in other ways; for example intellect v. feeling, masculine v. feminine, classical v. romantic, or Apollonian v. Dionysian. In painterly terms we might as extreme examples look at Edward Hopper, Magritte, Ingres and Poussin as image painters and Jackson Pollock, Masson, Delacroix and Rubens as oceanic painters. One important stylistic advance occurred towards the end of this period, my use of the colour black. Many of the painters I have admired most- Matisse, Klee, Pollock, Beckmann and Manet have all been masters in the use of black and I do seem to have developed a taste for pictures where bright colours are intermingled with and mitigated by darks. But my first use of black as a unifying element came about by chance, I rather stumbled on it when one night I tried using on a canvas a litre tin of gloss paint which I had bought at Decormecca in the Whitechapel Road and which was left unopened after one of my lousy painting and decorating jobs!

In order to find one’s place in the infinity of being one must be able both to separate and unite.

I Ching hexagram 3 Chun Difficulty at the Beginning.

Of the series of odd and synchronistic events in the last months of 1984 and the early part of the following year which led to an entirely new way opening up for me, I will give only a very brief outline here. However I did produce in rapid succession eleven triptychs, Screen no.1 and three large Trigrams.

It was no precedent in pictorial art that led me to this watershed, I found it instead in the study of form in musical composition, an art dealing with progression in time rather than space. With separated and sequential images came freedom from the need for the single masterwork, which in time led to the elimination of the instantly recognisable trademark style so beloved of art historians, critics and dealers. The realisation of a new way ahead was sudden, though beneath the surface new ideas must have been germinating for some time (The Triptychs of Max Beckmann at the Whitechapel in 1980 had been a revelation). It was during a visit to the family home in the unhappy period after the death of my father on a day of dull Autumn weather. I was helping my mother with house-work and by late morning we had got around to the sitting room and as we worked we were listening to the radio -the third programme, when Beethoven’s Diabelli variations came on. The announcer described how the great man had taken Diabelli’s unimpressive little waltz and utterly transformed it over 33 stages and I had the sudden certainty that I could do something like that. I had just completed a painting which had something different about it entitled -Lust Maddened Moles with Pubic Hair! Upon my return to London I used this charming work as a starting point for a series of eleven triptychs, based on broadly romantic themes such as Sleep,Gardens,Wine, Love, the Night etc to which I gave the modest title Wonders of the Universe (I had just read Mann’s Doctor Faustus). By the time I had in the new year started on my Trigrams and Screen I had discovered the string quartets of Bela Bartok and I used many of the formal devices from these in the complex layout of these successful new works. Through the process of formally separating different parts of a work I started to see an intellectual way out of the tangled skeins of massed paint that my works had become trapped in. This little distance allowed me to be able to study with some objectivity just what was behind these swirling and spiralling Dionysian energy trails which we see in Pollock and other expressionist artists. Many years later I saw the impressive Cold Mountain paintings of the 1980s by Brice Marden where a similar sort of dynamics seems to be at work. A curious footnote to this is that when in 1998 we began those coded portraits (which Louisa persuaded me to call Souvenirs rather than my original ‘Masters of the Musical Renaissance in Britain 1900-1950’) in which we used mathematical means, very much the same spiralling configurations came through. I read The Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra at that time and wondered if these might be the same sort of cosmic energies that are contained within the intuitive (lunar) knowledge systems such as Tarot and the I Ching.

This period saw the culmination of my interest in Jackson Pollock, and reliance on that free-flowing oceanic way of painting; I never have moved away from it entirely and I certainly did not move away from it in a hurry, but in 1985 I found myself rather in the position of Pollock in his painting “Portrait and a Dream 1953” and the black paintings of that time.

It is interesting to wonder just what Pollock would have done and what pictorial themes he would have developed had he stayed sober. What we can be sure of is that one so famous would have met with massive opposition to any new stylistic development by people in the art world; just look at the fuss when in 1970 Philip Guston – by no means the first name on Abstract Expressionist team sheet – had the guts to start saying something interesting, new and worthwhile.

In reading these notes about my earlier work I might give the impression that all my creations were carefully and consciously planned. The truth is that with most of the series of works I have started with only a very vague idea, often no more than a tiny aesthetic impulse; there are many false starts and it is usually only after a few weeks that I can see where I am going. The process of realisation proceeds along the same lines, at least where significant imaginative work is concerned. The beginning is obscure and it is then essential to be guided by intuition. After a while comes a period of clarity when content and form interpenetrate and this is when the best works are produced. Often it seems at this point that a painting paints itself and the work starts to sing. But this period doesn’t last indefinitely; all too soon the conscious mind starts to take over, I become familiar with the imagery and with repetition the enthusiasm and interest lessen–time to stop. For me this is the normal creative process, with work which is a good deal more figurative or abstract this cycle becomes more difficult to detect.

It might seem at first glance that I have produced a bewildering multiplicity of styles and subjects. This is a consequence of my attempts to start each new work from an entirely new standpoint. When I use the term work in this context I mean a WORK which is made up of a number of individual often small works. There are many advantages to creating a large work from small parts; on a practical level much ground can be covered quickly, materials are relatively cheap and storage easy. More importantly when I am caught up in a sort of guerrilla warfare between the conscious and unconscious mind, adaptability and simplicity are paramount. The essential thing is to not tarry. I can see no merit in developing an instantly recognisable style, often producing huge works and then plugging away at it with little variation for years while the power and energy drains away. Anyone with half a brain should be capable of understanding the implications of a new creative undertaking relatively quickly-exhaust the possibilities and without too much haste move on to other new and exciting things. Imagine a situation where Beethoven overjoyed at producing the famous four note motif that opens the fifth symphony never produced any more original works, just variations on that one theme. Yet so many artists today needlessly limit themselves in this dismal and timid way. If we could view life in its entirety as a tremendous romance about which there is so much to learn both of oneself and others around, and unknown worlds of wonder and incredible beauty to be discovered and expressed in some form we surely wouldn’t want to mess around. When Howard Hodgkin had a retrospective at the Serpentine in 76 I mentioned to one of my former tutors Adrian Heath that it seemed to me that Hodgkin’s work, unlike most contemporary painters at that time, might in future develop in so many varied and exciting directions. Adrian laughed and said “He has found his trademark style, its been accepted-he wont change now, at least not in any significant way, that’s all you need to do”.

Working on a smallish scale tends to lead naturally to a kind of art both personal and intimate. In the 1970’s young British artists and students were producing massive versions of John Hoyland or Frank Stella or even worse Hans Hoffman but I knew that this was wrong for me. Fine and impressive as some of these things were they said almost nothing to me about my life or interests; I wanted something different but I wasn’t at all sure how to achieve it. I think that the universal is best reached through the close at hand and that by sneering at or angrily rejecting and being too negative about one’s own history and culture a huge amount of essential creative energy is lost. The British have developed over the ages an almost unique poetic identification with their home soil, full of rich age old memories and associations, and I think it important to understand and learn about and above all protect and nurture these things so that our art develops in a natural and organic way. Views like this were deeply unpopular when I started out in the ugly, dark and depressingly political 1970s and probably still are today. Strangely enough while I enjoy British music and British writing I am not a great enthusiast of our home grown painters. I think the best of our recent artists are Patrick Caulfield and Gilbert and George; both say what they need in a straightforward, clear and unsentimental way. Of the generation earlier I would choose Francis Bacon and Roger Hilton. My own view is that both were essentially humorous artists- the gawky humour of Hilton is easy enough to detect, but I also view most of the figures in Bacon as comic inventions, and both men were very much products of their time with self destructive tendencies which I feel did a lot to lessen their achievements. With Bacon this led to an annoying repetition of themes. It is interesting to note the usual formula in his paintings – large areas of bland graphic style background denoting I suppose existential alienation contrasting with fine intense areas of painterly work usually around the faces where he employs a series of angry and wristy little brushstrokes which I always think leave his portrait heads looking like younger cousins of those unfortunate creatures on the right side of Picasso’s Demoiselles d Avignon! With Hilton it is a case of what might have been; unusually for a British artist he was both intuitive and a fine colourist even with all of that brown and ochre. Boozing dissipated his energies and I have noticed that his best work fell into just three short periods at roughly ten year intervals: the bold abstracts of 1953-4, the works of 1963-1964 including Oi Oi Oi and the blue painting that won the prize at the John Moore’s and the series of small late gouaches started in 1973. Surprisingly I have in recent years come to quite like the scratchy home counties landscapes of Carel Weight; personally I am not really interested in the funny sort of human dramas going on in most of these pictures but I enjoy the settings of mid century suburban England which in themselves are like bits of social history and remind me of the poetry of Philip Larkin and maybe even more of John Betjeman. Further back Sickert was in my opinion by far the best of his generation, a wonderful and intelligent painter. My other favourite British artist of that time is the neglected Sir William Nicholson father of celebrated and I think overrated abstract artist Ben Nicholson. Take a look at his huge painting Canadian Headquarters Staff of 1918 – a real tour de force!

The story behind the Guidelines below is as follows: at the end of the 1980s I started collaborating with Louisa Hutchinson on some fairly modest scale works which turned out to be a lot of fun and very fruitful. One day I jotted down 12 steps for painting; encouragement for our keeping our work fresh and warnings of the most usual pitfalls rather like the 12 steps of programmes such as Alcoholics Anonymous. When last year I started compiling these notes Louisa thought it would be good to put these guidelines in, unfortunately having kept them safe for years they were nowhere to be found. Having supplied a new list from memory (interesting to note the differences over nearly 30 years) the original steps were found copied in an old diary!

1. Relax and be happy.

2. You are not in control.

3. Attainable goals.

4. From the start, take what comes seriously, even that which seems ridiculous or grotesque.

5. There are no mistakes, just sometimes we are not sufficiently interested.

6. Concentrate on the marks not so much the image: enjoy the means and forget the end..

7. Not too much making up.

8. Careful of arabesques.

9. Be ready to do things you normally wouldn’t.

10. Keep it clear and simple.

11. Don’t worry about what people suggest.

12. BE HAPPY. You are a channel.

1. Relax and be happy, you are not in control. Remember that you are a channel.

2. There are no mistakes, only sometimes we are not really interested.

3. Do not overwork. Your painting may be finished sooner than you think.

4. Keep it simple. Painting is a visual art, if it looks good it probably is good.

5. Beware of trying to repeat a successful formula.

6. Avoid painting when tired or overwrought.

7. Start the day’s painting in a quiet methodical way, but if a breakthrough occurs seize the moment! Work fast.

8. No matter how serious your intentions retain a spirit of playfulness and simplicity. At all costs avoid the Faux Naif.

9. Always be prepared to discard. Have the courage to destroy and start again.

10. Do whatever it takes technically to surprise yourself. If you’re not excited nobody else will be.

11. Limit your palette. Less is more.

12 The image will come when you stop trying so hard. It’s already in the bag.

56 works Oil on paper 24” x 36”

Following the breakthrough in my work from 1984 to 1985 I tried to work out the possibilities opened up by this sudden burst of new ideas. Unfortunately the attempt yet again to do everything I could on a single large canvas proved a failure and I destroyed most of it.

It was only in the 56 Figure Pictures of 1989 that with a reduction in size, a limited palette and a single unified theme that I achieved anything satisfactory. I worked very fast and in a completely spontaneous way, allowing for any imagery that came through.

22 Paintings oil on canvas 50” x 60”

At a time of extraordinary difficulties painted in my large warehouse studio in Wapping during the very hot summer of 1990 which I knew would be my last in that place. I tried here to make the empty spaces in the painting as important as the painted areas. I had a fascination that summer for all things Oriental; poetry, pottery and painting which was so powerful and unexpected that it was as if I was under a kind of spell! Whilst a feeling of vague mystical potentiality pervades these works toward the end something is added and in the final one “View”, the eye is drawn toward a distant still centre while all around is abundant dynamic nature, tremendous in energy!

The title refers to the absence of sunlight and sunshine in oriental art and in a general way refers to those still, grey, overcast days, especially those that occur at the end of Summer and the onset of Autumn when the veils that separate the seen from the unseen world are at their thinnest. Anyone who has spent much time out of doors will be familiar with many such quiet days when it seems that all of nature falls into a strange mood of expectancy as if silently watching and waiting for some great cosmic drama to unfold.

42 works. watercolour on paper 12” x 18 “ and 18″x 26″

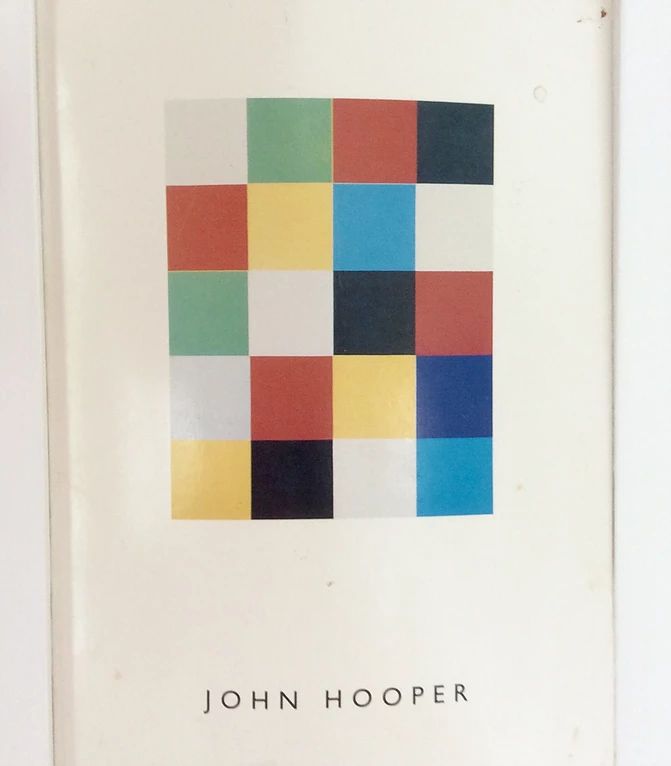

These were a respectful nod in the direction of fellow Wapping artist John Hooper whom we admired. Painted at the same time as the large canvasses, these strictly formal works provided a counter-balance to the rather atmospheric landscapes. I worked out a happy solution here which was both simple and harmonious; the smaller ones were divided into 6 parts made up of 4 colours which never join and the larger works were divided into 8 parts made up of 6 colours.

260 works, watercolour on paper 24”x 18”

The first works in my new studio in Bethnal Green. The basic idea was derived from these two Paul Klee paintings Monuments at G and Before the Snow both of 1929.

As the title suggests this series was about plants. They also look at the weather and meteorological conditions generally, things of such importance to the gardener. Most typically these consist of a rapidly drawn lyrical subject on striped grounds which in themselves also form a rhythm; an effect rather like a song with its vocal line and piano accompaniment.

55 parts Oil and cement on card. Approx. 3”x 6”

This is a series of tiny fragments which were originally planned to be shown together. Here we see the vastness of interstellar space expressed in an absurdly small format. After the lightness and grace of Botany, I wanted to change direction so I laid down a rough cement base on which to work; -imagine attempting to dance a ballet on a ploughed field. From out of eternal darkness forms begin to emerge.

119 parts oil and cement on card Approx. 3”x 6”

Closer to home in space and time, these were the largest of the three sets of Mosaics; a lively group of images taking the germ of an idea and developing it in the very simplest way. In all of these series of Mosaics and others it doesn’t do to take things too literally, and it helps to know something of the mysterious world of symbols!

62 parts oil and cement on cardboard. Approx. 3 x 6

Sometimes with secure delight

The Upland Hamlets will invite

When the merry Bells ring round,

And the jocund rebecks sound

To many a youth and many a maid

Dancing in the chequered shade.

Milton

Very deep is the well of the past. A light-hearted look at a time when, unlike today, man lived in close harmony with nature. This unwieldy trilogy of Mosaics has a formal pattern where Mosaics 2, which comprises some strange but largely contemporary imagery is flanked by two parts which recede a very long way- – the first into the darkness of cosmic night and the third into the equally remote depths of the past.

134 works oil on paper 18”x 12”

These are small works where the comedy element is of various types from the philosophic to the ridiculous, mainly fuelled by rancour and disgust at the evil stupidity of men. At this time of the early 1990s unconscious imagery of all kinds seemed to flow effortlessly, my hardest task was to order and assimilate this teeming mass of material.

49 works oil on paper 24” x 30”

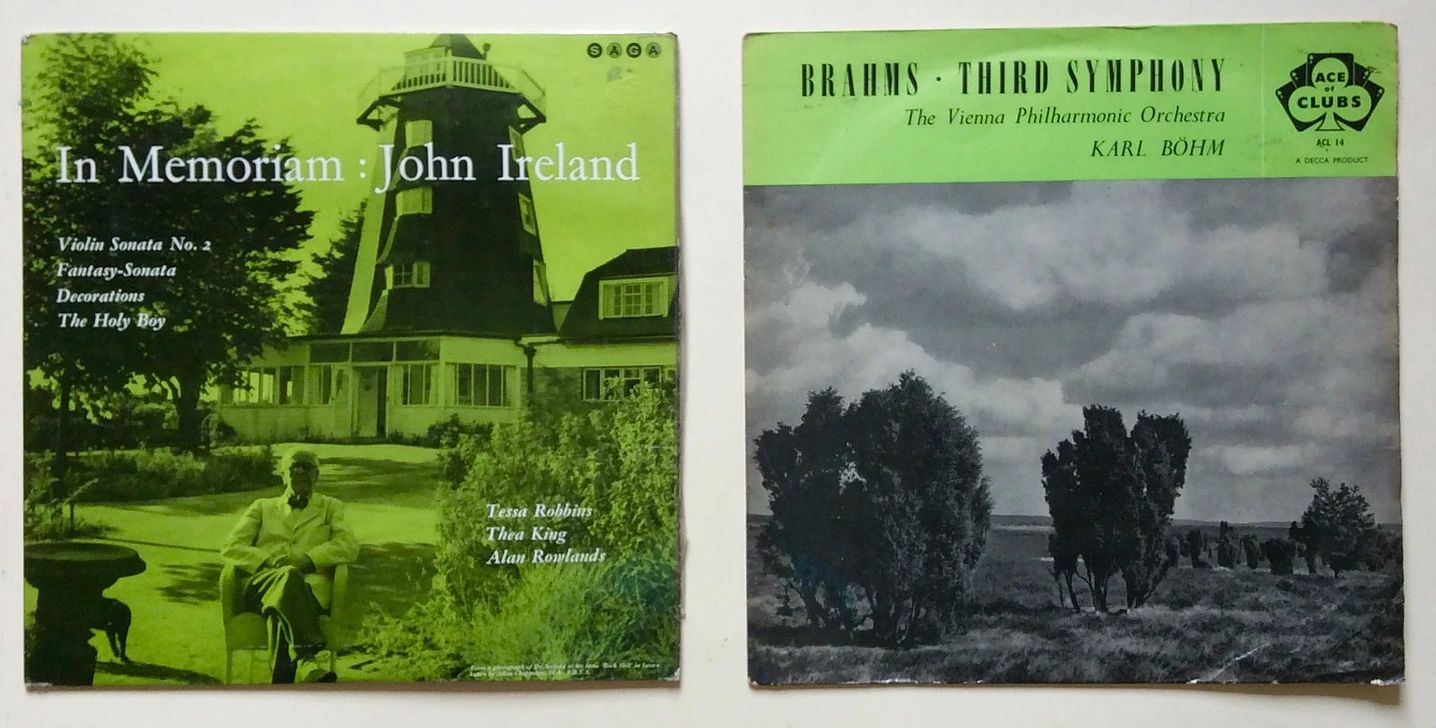

I had these two green often played LPs in my studio at the time. My intention was to paint a very straightforward even bland landscape such as you might see if you glanced up from your novel and looked out of the window of your train, but quite unintentionally, something from a far more distant past kept coming through.

22 works watercolour on paper 8 x 24”

Painted in the Spring of 1997 in my tiny flat in Bethnal Green. They are experiments with numbers, systems and codes which could be worked up later on a larger more ambitious scale.

18 works Acrylic on canvas 20” x 26”

An unfinished group – the original plan was for 24 paintings.

The final and highest point of our studies in code and number sequence. Painted with Louisa Hutchinson over what was for me an unusually extended period. The idea for the subject came from musical cryptograms such as the famous BACH motif and Ravel’s Menuet sur le nom d’Haydn of 1909.

The paradox here is that the further we moved away from story and image and became more mathematical, the closer we seemed to get to those dynamic laws to which all nature adheres. It didn’t occur to me until recently that there are some similarities here with the work of one of my former teachers, Systems painter Michael Kidner. A nice man, but an idealist and intellectual and not someone I often saw eye to eye with, so this convergence was quite unexpected. Another stylistic connection -a closer one is with the 1960s lozenge paintings of the American Larry Poons; these used to be bracketed a bit misleadingly with Op Art and have rather faded from sight, which I think is a shame as they are among the least dated and best products of that turbulent decade.

98 works oil and cement on board approx. 3” x 6”

A re-working almost 20 years later of works I had rejected from the series Asteroids and Concertino Pastorale which had originally consisted of over 100 parts each.

245 images oil on cardboard

Painted at a time when all the talk was of austerity after the financial crash of 2008 using the very simplest and cheapest materials, everything including colour pared right down to a minimum.

My early years were spent in that unfortunate and marginal part of Essex which even in those days was beginning to suffer from its closeness to the ever encroaching city. A mile away down the marshes was that broad reach of the London river described in the opening pages of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and we went there often to watch the ships. The Tilbury branch of the LTSR with its steam engines ran past the bottom of our grandparents’ garden while northward by low hills and woods were sand and gravel pits to explore, each with their own assortment of cranes, washers and tipper trucks. Despite increasing industrialisation the area was still fairly rural and we grew up surrounded by tractors and farm machinery, cottages, ancient farms and overgrown trackways. My brother and I for some reason revered the slow mouldy and jolting; the old and characterful and eschewed the flashy and modern, so cars and aeroplanes had little place in our imaginative universe. At that now distant epoch the British scene was full of such relics, but the pace of change speeded up at the end of the 1950s and soon under the hammer of the modernising zeal (which was really often a kind of pea brained barbarism) they had been quite swept away along with much else of value. But while they remained we watched, noted and studied these things and drew them throughout all of the years of our childhood.

In this work there are also some landscapes, scenes of lonely broad-skied marshland or of the open downland where are found those dykes, barrows, camps and the age-old trackways of long vanished people.

60 works. Oil and paper on board

Colour returns here, in what had been originally planned as very simple paper cut-outs. Although I quite like the idea of minimalism and in some ways my works do at times overlap with it I’m not emotionally at home there. Minimalism at least in the Plastic Arts nearly always ends up looking dull, colourless and uninteresting. I suppose I see in art as in life such severe asceticism as permissible only as a corrective to excess but nonsensical as an enduring condition. I had these things hanging around for quite a while, looking like a set of decorators colour charts and it was only when I added the curious images that I was able to achieve something worthwhile! Minimalism seems to derive much of its spiritual justification from the East and a form of Zen Buddhism- we all know the sort of thing-the sound of one hand clapping and the heavenly music played on a Zither without strings- and I think implies a retreat from and to an extant a rejection of everyday reality. However whereas in the East silence and invisibility were understood to contain limitless content and potentiality-albeit unseen and unheard, in Western culture this usually translates as a kind of quasi-spiritual reductive Puritanism. The so often empty and heartless results of this kind of thing are familiar enough: such Oriental dabbling is usually harmful though earthy or vigorous natures may escape from it without too much damage.

64 works

I began this work in April 2013 and completed my 400th and final portrait of actress June Thorburn (1931-1967) on the final day of that year. In the production of these portraits I developed a new technique which involved lots of rubbing out with turps and rag- in fact more rubbing out than putting on. Using the laws of chance these paintings were then arranged into 64 parts, 48 of 5 and 16 of 10,each set out vertically. An unusual feature here is that not only is chance employed to decide which works go together but the final arrangement is left to the owner, so distancing the eventual look of the work from the maker. So this becomes a three part invention–painter, chance and owner! The portraits are of cultural figures, politicians, sportsmen and a few villains to add spice. Interspersed with these famous ones are a few friends and acquaintances. When most normal kids would have been reading comics, I spent hours poring over encyclopaedias with their pictures and biographies of great men ( for some reason I can from that time recall only two famous women: Florence Nightingale and Marie Curie! ).

12 paintings 10”x 100”

By the beginning of 1995 having completed in the previous five years over 900 original imaginative works I felt that I had begun to run out of puff. Some years before, the gallery owner Rebecca Hossack, upon seeing some of my medieval type figures suggested that I illustrate some old writings. Being at an impasse, I remembered her words and started looking at Chaucer, Milton and Skelton among others before deciding on the Eclogues of Virgil. I then produced 12 large scale painted illustrations with accompanying text.

Although at the time I found some interest in the new element of restriction and control in making these works, I never in any way felt satisfied with the results. Cleaning up the attic in early 2015, I found these paintings, cut off the written part, re-worked just about all of the imagery and kept just the original format. Now in the first part I start with two evening reveries flanking a sleeping figure which correspond with the final part where the grave of the poet is framed by two scenes; one of a bald hillside at night with animals before an approaching storm and the other depicting a lonely moonlit trackway. I employ two painterly styles throughout, simple bold planes or a gently rippling pointillism, this contrast is most clearly seen in parts 2 and 3 which show respectively events by the sea and in woodland.

The overall mood of regretful nostalgia is I think an unusual one for me but is appropriate in this lament, not for some idyllic golden age, but simply for a now lost Pastoral time when men lived much more in accordance with their instinctual selves

Oil on canvas 16″ x 20″

Begun at Easter 2015 as a small set of landscapes in the English style, these became 48 Dorset scenes in the olden style, eventually becoming 100 views of Dorset and completed just before the New Year with a picture of the Frome Valley in flood.

These are all generalised scenes focussing largely on the man-made landscape including 11 of seaside views and 8 of villages with thatched cottages.

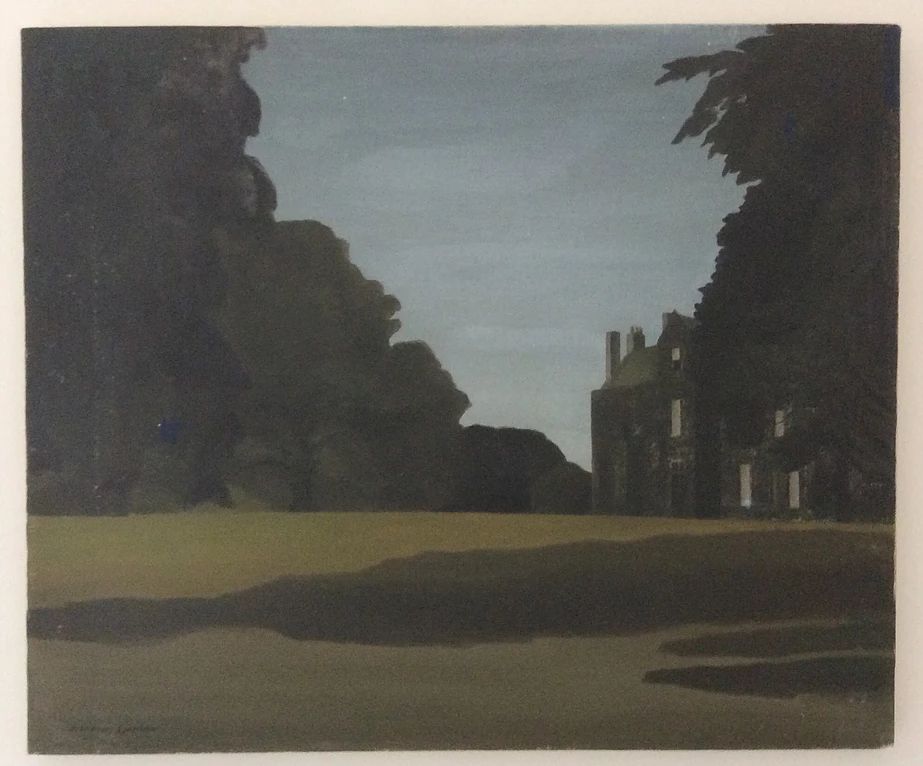

I got the idea from this painting “Chalmington 1934” by local artist Norman Lupton which I had bought for £10 in the Dorchester car boot sale. It says something about the state of aesthetic appreciation and intelligence in this country that this lovely evocation of a late summer evening could be bought for such a pathetic sum! But also comes the thought that whatever is done with love of beauty though seemingly discarded or unnoticed may perhaps awaken an echo or response even at a distance of many, many years.

What I was really trying to do here was to produce the sort of simple landscape paintings which I love best. So you will see similarities with works of, among others, early Van Gogh, Max Beckmann, Sickert, Albert Marquet and Edward Hopper.

I’ve also made some references here to that neglected area of British painting – Victorian sentimental landscapes.

Old photographs from local history books provided the basis for the majority of my scenes, and I must say that the hardest and certainly the most laborious task was finding suitable material. The really good black and white photographs seemed to suggest the appropriate colour scheme; I used a key for each work of not more than 2 or 3 colours plus earths and greys. Of formal qualities not much needs to be said as they are simple, straightforward and healthful in a vigorous, outdoorsy sort of way.

100 works

cut paper

Now that’s what I call Modern Art – lots of sharp angles hardly any subject and plenty of bright colours!

153 works

cut paper

A set which grew out of Collage 2016 with which they share much of the same material, the main difference here is that the subject is animals and their plight in the modern age. It is natural with torn and cut paper to have a broken and fractured picture plane, the chief job here is to harmonise the various parts in a way which is both fresh and new.

Formally classical and restrained, happy colours, difficult and troubling subject matter – this could be a bumpy ride!

Cut paper on card

333 works

Started in March 2017 when I one day by mistake cut through three pieces of thin coloured paper instead of what I thought was a single sheet, leaving me with some identical shapes. These small works consist of repeated forms; excepting Op Art and some bits of Minimalism this is a pretty unusual thing in the plastic arts but in Music familiar enough in the form of Canons and Fugues. It might be assumed that with such mechanically limited means things would quickly descend into brainless pattern- making inertia! These technical studies I hope show that this need not be the case. To achieve balance whilst avoiding uniformity a number of devices are employed, here among others you will find sequences, interrupted sequences, regressions, cross and counter rhythms, shuffling and sliding’s, mirrors, inversions and echoes, leading sometimes to strange figure- ground ambiguities and unexpected metamorphoses. From these little studies we might take thoughts of order further and look at the importance of establishing the correct time and place for obedience to authority and dissent. It wasn’t rebellion that led to the horror of a civilised country like Germany embracing Nazism, rather it was mass submission to the insane Father will, and very recent history shows how many seemingly just and popular uprisings have turned into appalling disasters.

Taken as a whole these three Collage\Cut Paper works of recent years show a transition from the stark simplicity of Collage 2016 where we see nature marginalised and dominated by man-made constructions and the increasingly complex imagery of the second set where the threat to the Animal world is made explicit, to a rather more happy and harmonious relationship between man and nature in Miroirs, characterised by a generally higher level of organic integration and rhythmic intensity.

Wire. 9 works

Sculpture ! What a wonderful thing. Even the most modest constructions provide an almost unlimited amount of viewpoints and images – so many in fact, that it becomes difficult to verify the existence of the object at all. A little group of nine works made with wire which show a gradual increase in size and complexity.