JOURNEYS

The way westward following the course of the Thames from our tiny railway station to the City took less than an hour yet despite this proximity London occupied little place in our lives, indeed I can count on the fingers of one hand our childhood visits there. Of these family outings to places like the Science Museum I can remember virtually nothing; memories of a view over the city from what I think was Westminster Abbey and a wonderful boat trip on the then busy river from the Tower to Greenwich are just about all that remain with me, but I can recall very clearly the early journeys by steam train on the old LTSR, passing in turn Tilbury with its docks, Grays, Purfleet, Rainham and Dagenham: scenes of increasing industrialisation that had us children darting from side to side of our single compartment hoping for a glimpse of some unusual engine or activity on the private sidings or narrow gauge systems that the huge factories all seemed to possess in those days. After Barking, as we sped through Bow, Stepney and Limehouse we gazed with fascinated horror at the filthy blackened Victorian tenements and slums, which in those post war years were scenes of real squalor and deprivation.

It was not until I had started art school foundation course at Thurrock Technical College years later that I got to know London. Every term there was a coach trip to the capital, but unlike the train these road journeys seemed dreary and interminable and emphasised the alien vastness of the place. The purpose of these excursions which continued when I went to Bath Academy of Art in 1972 was to see current shows and acquaint us with the London art scene. At first we students travelled around in small groups fearful of going astray or even worse missing the coach at the end of the day, but later with familiarity we became happy with solitary explorations. One advantage I did enjoy was that I was entirely open to whatever came my way—anything that helped to distance me from childhood and horrid schooldays was welcomed, and I treated this abundance of new discoveries completely without criticism or discernment—a very happy time! It is strange that of all those early visits I can remember only the very first; we somehow found our way to the unloved concrete fastness of the Hayward Gallery (this must have been late 1970) for a show of Kinetic art of which I knew absolutely nothing and this was coupled I think with Olivetti Concept and Form—graphics from Italy. I was enchanted by the space age mystery of it all; a strange odour like the very smell of modernity seemed to hang about it.

What other places did we visit on these college trips? The outlets were very limited compared with today. Apart from the intimidating Hayward which was then at the centre of everything modern and avant-garde, there was the essential diversion to Pimlico and the Tate, but with so much of the contemporary to see I only occasionally visited the National Gallery and never the Royal Academy (home as we saw it to a load of bloody old fogeys). We soon realised that all the important commercial galleries were in Cork St and its environs—Tooth, Kasmin, Redfern, Waddington and close by in Albermarle St. the impressive Marlborough. On one occasion we encountered one of our tutors Michael Kidner coming out of the Redfern who said with great glee “you’re wasting your time, you will never find anything in here” A cup of tea and sandwich in Queen’s café and then a trawl around the galleries—we were in the very heart of the British Art World! The hope of securing a one-man show at one of these prestigious places was just about all we students aspired to—a real sign of having made it as a serious artist.

It was not long before my innocent and uncritical outlook changed; with knowledge came discernment, and I entered a phase in which I still find myself languishing where my gallery visits invariably left me frustrated or angry. Despite the odd happy surprise, why was it that most of what I found in these places left me dissatisfied? It was as if in some way modern art was a kind of cleverly organised scam or con-trick and that many of the productions even of famous artists were often not that good.

NO GROUNDING IN THE CLASSICS

By the time I started at Bath Academy of Art aged 18 I had learnt a lot about modern art. There in company with a group of like-minded and ambitious fellow students it soon became clear that while we were learning so much about important painters we should surely acquire a similar knowledge of all other branches of culture; writing and music as well as a basic understanding of politics, science and philosophy. For my own part I felt that these undertakings were a search for a key that might open doorways onto some exciting new world of the imagination, free from all that was mundane or commonplace. The novel properly read and imaginatively lived through was to become for me the best means of accessing those realms beyond, especially during the poverty-stricken and miserable years in London; however this interest in fiction dates only from this time, as a child my reading was of quite another sort. My brother Vincent was four years older than me and was an imaginative boy-he invented an entire alternative island state complete with its own political hierarchy, geography and transport systems of which he made copious lists and detailed drawings. I followed these inventions with enthusiasm, especially I loved watching him drawing and became a good copier quite early on through his influence. I also grew up surrounded by his books. There were many examples of the Observers and Ladybird series, and the excellent little Ian Allan volumes on trains, ships, buses and lorries. We had a set of beige and maroon coloured encyclopaedias called The Book of Knowledge which had on the spine A-BON BOO-CRO and CRU-GERA etc. which always fascinated me. There was also a big children’s encyclopaedia which most unusually for that time was in full colour and from which my father read to us about the ancient Persians, of Ur of the Chaldees and the dawn of civilization in the lands by the Tigris and Euphrates. This long lost volume also contained a set of wonderful artists’ impressions of scenes from the planets, strange landscapes, where Earth was depicted by a distant view of an English town amid chequered fields and rolling hills! There were two combined volumes of the War Illustrated on the very cheapest paper from the dark days of 1939–40, and some Odhams press productions from the years just after the war including The Miracle of Life and my favourites The Countryside Companion and Lovely Britain both edited by Tom Stephenson of Ramblers Association fame, the former consisting of chapters by various experts on just about all rural affairs, the other a county by county guide to the topography of Britain which was rendered obsolete by the imbecilic county boundary changes of 1972.

My experience of any fictional writing or anything approaching serious literature was extremely limited up until I was eighteen. We had the Rupert Bear annuals around, they had belonged to my brother and I knew them from the earliest time; I have never much liked anything too made-up or fanciful and these had for me just the right blend of countryside realism and magic. Later I borrowed a few space fiction tales from the school library which in common with some of the ghost stories I also read were enjoyable up until the point where anything dramatic actually occurred. In the classroom we read Lord of the Flies, Pride and Prejudice and the tedious History of Mr Polly by H G Wells, while ‘struggling’ best describes my efforts with Macbeth, Twelfth Night and Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer! My father passed on to me a story of Daphne Du Maurier set in Cornwall, Cider with Rosie and a romance by Scotch writer Hume Nisbet called The Divers and that I am afraid was about it. Oh, and I almost forgot our enormous illustrated family Bible flogged to us by the Catholic priest on one of the annual visits to his distant flock.

PENGUINS

The Penguin paperback series was our gateway to literature in those college years, and we felt that everything significant was there and that if a writer was not published by Penguin he probably couldn’t cut the mustard! The people running the business took care with every aspect of the books. The size was a compact 4”x 7”, small enough to fit a pocket which I suppose was the original purpose of such things although with Tolstoy and others you ended up with quite a fat awkward to hold object. The covers were nearly always of a painting, usually from the same period as the book and intended to provide a visual equivalent to the story and these more than anything helped my discovery of literature. If I liked the cover I bought the book and if the cover looked dull as with that dry old bugger Henry James, then I usually avoided it; this intuitive visual method let me down only once with Auto da Fe by Elias Canetti; poor stuff and one of the very few books I didn’t finish. Older literature including those Russians which we all read and discussed (I read the entire Crime and Punishment over one long winter weekend huddled by the hissing gas fire in my hostel room overlooking Corsham Court) was in black covers; these were Penguin Classics and those with grey backs were the Penguin Modern Classics which we prized above all others and there were also the Penguin Modern Library in orange for books of lesser importance. There were a few unexplained exceptions to this general rule—the stories of J D Salinger were completely silver while the novels of Gunther Grass were a sort of goldy bronze. Reputations come and go and in those now distant days D H Lawrence was, thanks in part to the critical work of F R Leavis, probably our most widely read author; we certainly looked on him as the great man of English literature. He is not held in such high esteem anymore, but I ploughed through many of his powerful but not always enjoyable stories. The more advanced students all possessed a copy (often unread) of The Glass Bead Game by Herman Hesse and everybody seemed to own a copy of Kafka’s Metamorphosis and other Stories (the one with the Max Ernst print entitled Le Hibou on the front).

Bookshops were important places; I hardly ever failed to buy something in Bath or London, and looked with pride on these acquisitions as collectable items and not just a collection of stories. I think it is interesting that the high point of the Penguin paperback (1960–1985) coincides with the great years of the Long Playing Record where words and music were enhanced by their presentation in a desirable aesthetic object. Having built up such a successful publishing strategy it seems incredible that during the 1980s Penguin just threw it away and seemed to do all they could to become commonplace. The cost seemed to go way up, the format increased in size, photographs now replaced the paintings and where these remained they were often changed to inappropriate images. The intelligent and reliable system was sacrificed to trendy formats that might appeal to the mass market.

COMPENDIUM

It must have been as a result of a recommendation rather than chance that I found my way sometime in 1973 to the Compendium book store in Camden Town which was the place for all that was considered radical and avant-garde. Hurrying through the sections headed Politics, Drugs and Alternative Society I went straight to Poetry, Fiction and the Occult and over the next few years bought many things that were not sold at the ordinary high street outlets including unusual books from US publishers, some reputedly sexy stories of Henry Miller and a largish textbook about Carl Jung which was left mainly unread. Other notable acquisitions were Death on the Instalment Plan by Louis Ferdinand Celine, the I Ching in the Richard Wilhelm translation, Artaud Anthology, A Philosophy of Solitude by John Cowper Powys, Erections Ejaculations and Exhibitions of Ordinary Madness (on the cover a photo of a awful looking Charles Bukowski) and a couple of works of Arthur Machen: the London Adventure and a fine collection of tales including The Great God Pan—an incomplete list but enough to give a flavour of the exciting discoveries made in that place.

A whole imaginative world, largely an occult one opened up and I pursued this alongside my other studies. It was as if I was wandering down one of those trackways of verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways which provide a secondary path into some Renaissance landscapes but whose narrative purpose remains a mystery. One can occasionally find these symbolic hidden tracks in pictures from about the time of Bellini and they may be traced through the Venetians and northward to Rubens, Ruysdael and Watteau. (It may be said that almost everything of Watteau takes place down one of these byways).

The important thing is that we turn inward and learn something of these mysteries and open ourselves to spiritual change that we might then turn back to the outside world with objectivity. Over there in the series of Mosaics and others, I tried through the use of allegory, metaphor and symbolism to delineate as broadly as I could the remote regions of the psyche, what might be called the landscapes of the mind; a pair of green disembodied wings lies on a table, a man punts across the sea of consciousness on an old shoe, another has three heads; he plays rugger with one, another sits on his shoulders and he has the third up his arse. Not everything in this magical shadowy realm is benign; another path forks, this way potentially leading to a kind of death in life , the nightmare of madness and self- destruction. Finally there was one other kind of book we all had, perhaps for an art student the most important of all–illustrated books on painters and painting. The reasonably priced, black covered paperback series of Thames and Hudson gave us a straightforward overview of the often bewildering and strange world of Modern Art in much the same way that Penguin paperbacks had with the world of Literature. The BIBLE among these was Herbert Reads Concise History of Modern Painting, which we all owned; I have never had any any book which has been leafed through or pored over as often or disliked as much as this awful thing. I have always been just as happy looking at pictures in good quality reproductions as in an overcrowded gallery; when I look at certain images I experience an altogether pleasant sort of commotion in the brain as psychic energies are released and this can be got perfectly well from pictures in books (among some notable exceptions to this are the big early paintings of Matisse such as The Dance and Red Interior which look ordinary in reproductions but when seen are wonderful- huge miracles of colour).

POETRY

It was not until I was in my early twenties that I realised just how much what we might call the sublimated poetic impulse had driven my many interests and enthusiasms, although the actual reading of poetry has never been of great importance to me. I think poetry comes across best when listened to or recited and as there are limited opportunities for this in these busy times I am like many people nowadays happier with shorter poems. Who today reads epics like Hyperion or Empedocles on Etna? I have a preference for relatively modern verse; however my two favourite poems are To Autumn by Keats and Matthew Arnold’s Dover Beach. As my natural affinity is with music and painting rather than the written word, most of the poetry I have learnt is through the medium of French, German and British Classical Song.

THEATRE / CINEMA

Essex boys in those years just after the last war had little opportunity to visit the theatre and for us there was no Pantomime or Circus either, while at school there were no singing or acting lessons although I do seem to remember coach trips to a couple of not very interesting Shakespeare Comedies. During college days theatre was never considered at all, and I must say that since that time although I have seen some very good plays there have also been far too many expensive disappointments.

Although family visits to the cinema were rare, I was always enchanted by the romance of the entire event and today still experience something of that same excitement. My mother always said that when she was young the glamourous Hollywood films were all that they wanted to see and that British films were definitely looked upon as second rate. But I have always enjoyed the Ealing comedies, as much as anything for those fine scenes of post war London with its bomb sites and boarded up buildings, and those gritty northern working class dramas of the late 1950s with their memorable black and white views of the grimy mill towns of Lancashire. The films of Michael Powell are about as good as any of the major works of post war European cinema, my favourite of his productions being the wartime A Canterbury Tale. My other best British film is about as dissimilar as it is possible to get, Nil by Mouth of 1997 directed by Gary Oldman and set on a South London housing estate. In the revision of all values which I experienced for a number of years after starting at college, mainstream cinema was despised and only art films or anything with subtitles was taken seriously; and it was at that time I first became fascinated by French cinema of the black and white era. At foundation course we were introduced to the Surrealistic films of Georges Franju and the early works of Luis Bunuel, Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or. At Corsham we learnt more about world cinema as the college took over the local pictures late every Monday night and showed films by Hitchcock, Pasolini, Wajda, Truffaut and Godard among others. Bergman was shown often, I clearly remember watching his gloomy masterpieces Wild Strawberries and Through a Glass Darkly and the Swedish master was generally considered as the most important director at that time. In my final year in the West Country a young and enthusiastic Robin Mariner arrived to fill the post of head of Film Studies and he introduced us to even more recent cinema. There was a series devoted to the work of the experimental filmmaker Steve Dwoskin and also an example of what must have been American Minimalism which consisted of 75 minutes of a camera silently panning around a deserted High School classroom!

MUSIC

I have noticed whilst compiling these notes a constant tendency to misplace events in time and to put them at too early a period of my childhood but feel sure in this case that it must have when I was aged eight that a brand new free-standing Radiogram arrived, I even remember helping fit its little feet; it was all fake wood and Bakelite with a dropdown door opening onto the turntable, the novel feature of which was a stacking contraption that would automatically release and play any number of records. Beside this were wire storage racks and at the top a complex and fascinating radio display with knobs for fiddling. At that time all we had was a selection of old 78 rpm discs, some popular songs of the 1950s; Mantovani and his cascade of strings was there, and also some Operatic Arias; I remember my mother playing a record of Italian Tenor Beniamino Gigli at high volume, the cover of which had a picture of the great singer looking disreputable in doublet and hose which I always hated. My parents would talk about Gigli and Caruso lamenting their early deaths and attributing this to the terrible strain on the heart that this form of singing caused and I wonder now whether these disagreeable experiences and stories put me off opera for life, as apart from Wagner and some Puccini I hardly ever listen to it.

Later we got a large box set, A Festival of Light Classical Music with the well-known picture of the orchestra pit by Degas on the cover, which consisted of 12 LPs with extensive written notes. How I used to pore over that booklet with its concise descriptions of the music and the mainly tragic stories of the great men, illustrated with pictures in sepia and a kind of ugly sap green of among others, wild eyed Mussorgsky, a furious looking Wagner, the dandy Offenbach whom I didn’t like the look of at all and our own Sir Edward Elgar sitting on a Malvern hillside all pride and hauteur! I think it must have been in Coventry in the momentous year of 1963 where each summer we spent a week with our Aunt that my Father bought from a music shop in the then brand new precinct the first proper LP record I had seen. It seems strange that with all of its post war rebuilding and wealth of proud Modernist erections including its new Cathedral, that I have always felt in Coventry more than anywhere in England a profound sense of the medieval- something like the feeling of the middle ages still lingering in certain German towns with all of their ancient buildings, strange festivals, craftsmen’s guilds and Hanseatic leagues. This LP was of Grieg’s Piano Concerto with soloist Robert Riefling. The attractive cover portrayed a scene of Norway with a man in a soft hat astride a rustic gate unlike any we had in Essex, gazing out across a level expanse of sunlit corn toward distant blue Mountains. Later another large box set arrived—the orchestral works of Beethoven which included the Violin Concerto which at that time was the loveliest thing I had ever heard. I bought my own first classical LP some years later from Bath; it was Mahler’s 4th symphony conducted by Haitink. I had up until then heard nothing of Mahler; he certainly wasn’t to be found in our Festival of Light Classics box set and I relied in those early purchases entirely on intuition or chance and of course the pretty pictures on the front! It is always a good if somewhat over-used device to begin an imaginative work with a journey and what better way to begin a lifetime of collecting music than with the sleigh ride of the opening movement marked Bedachtig-Nicht Eilen! A few other things followed—Debussy’s La Mer and Bartok’s first Violin Concerto coupled with his unfinished Concerto for Viola with Yehudi Menuhin as soloist were important discoveries.

I don’t think that even today England in comparison with other European countries is a particularly musical place. I remember very well the day my brother proudly brought back from school a recorder; it had with it a yellow cloth and a funny sort of miniature loo brush for cleaning and I will never forget the more or less dreadful sounds that came out of it! We had of course Carols at Christmas (Catholic ones) and the Mass in Latin. If God had a language it seemed only right that we wouldn’t be able to understand it so imagine my dismay when years later it was all translated and made commonplace, a bit similar to what happened with the new version of the Bible at about the same time. Among other good things we had the Thomas Aquinas hymn which began Tantum Ergo Sacramentum Veneremur Cernui which I loved and would sing aloud on many solitary wanderings and bike rides. I can honestly say that these scraps of music, incense, the lovely flowers put up on the Altar by the Nuns and the bright colours worn on their vestments by the Priest and the Altar Boys are just about the only happy memories of those all those years of grubbing around in Church.

I don’t want to overstress the importance of classical music for us at that period of the early1970s as by then popular music had developed incredibly quickly from 1963 (the year of the emergence of the Beatles and the Stones) and had branched into numerous forms; rhythm and blues, pop, and then rock and from there hybrid forms of progressive music followed; folk and jazz influenced rock, electronic, heavy metal, soul music, motown and the advent of reggae. You couldn’t be growing up in those days without being affected by this amazing cultural movement, however it was only when I started art school that I became aware of the extent and complexity of it all; up until then we had been reliant on the offerings of the radio and BBCs Top of the Pops, which of course played only the more commercial stuff which didn’t really matter as at that time much of this was mightily impressive. It is difficult to imagine today just how seriously all of this was taken; every student seemed to have LPs, in some cases really huge collections, and there were numerous discussions about the merits of various artists and just what their often obscure lyrics actually meant, as well as a healthy market in selling or swapping parts of a collection. One of my less successful of these Swappsies as we used to call them at Tilbury school saw the exchange of my copy of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks (one of the great records of the 1960s) with my friend Jeremy Young’s album of Hot Dogs, an offering by American acoustic guitarist Stefan Grossman! Sometimes a student near the close of term finding his money running out would reluctantly sell their entire stock and eventually by the 1990s most of these proud sets were chucked out in favour of that terrible piece of technology the cassette. But while it lasted what a fine thing the LP was!

The greatest shock of my early life other than being abandoned by my mother in the school playground on my first day at primary school was entering art school at Thurrock aged 16 and finding out that I shouldn’t address the tutors as Sir as we had at school but as Pete Geoff and Ben; and it was in this wonderfully liberating environment that over the next couple of years I made what I can now see as by far my most rapid advances in learning. Pop music with usually a bit of Jazz or Blues was an essential part of this mass of new impressions; it would be playing every day while we studied, which was especially good during those tedious Fridays given over entirely to life drawing. Some of my fellow students were very knowledgeable about the whole progressive music scene and they brought to college and discussed many of the newest things, also there were always copies of music magazines lying around- New Musical Express or Melody Maker. Their usual preference was for the US West Coast scene – Crosby Stills Nash and Young, Hendrix, Zappa, Beefheart, Jefferson Airplane, Tim Buckley, and the Doors among many others, most of which was new to me. At some point I singled out some unusual and delightful pieces and proceeded to buy my first two pop LPs: Santana’s Abraxas which had on its exotic cover a quote from Herman Hesse of whom I had not yet heard and Marrying Maiden by the San Francisco group It’s a Beautiful Day which unusually was led by a violinist David la Flamme. This LP had a picture on the back of the group surrounded by mystical eastern things like lanterns, masks and I think an Ouija board and on the album front a Chinese style depiction of a young couple with the girl on a mule and the 54th hexagram of the I Ching of which I was at that time totally ignorant. (One could write an interesting article on the way that things of eventual great significance first enter our lives unheralded or in unusual ways). As the 1960s progressed I felt that British pop rather lost its way and had a tendency at times to become pretentious (Sergeant Pepper, Tommy the rock opera and groups like ELP). However we still heard and enjoyed plenty of it and when I went to Corsham the heavy drinking evenings of our first year away from home were accompanied by the constant jukebox repetition of Bowie, Roxy Music and Thin Lizzy. The small town of Corsham possessed eight pubs and in our local, the Pack Horse, the virtually undrinkable scrumpy cider was only 10 pence a pint Watney’s Ordinary was 12p and their Special 14p, and on quite a few occasions I made my way across the 100 yards to my hostel on all fours pissed out of my mind and gibbering in the early hours of the morning after what in the West Country they referred to as a lock-in! Musically we now looked increasingly to New York and the movement centred on Paul Morrissey and Andy Warhol. Under the guidance of fellow student David Jones who was a Velvet Underground aficionado we all started to get interested in this gritty urban scene, buying and discussing in detail the latest albums and watching a lot of those self-indulgent Warhol films. Although I enjoyed the music there was a lot of the 70s scene that I wouldn’t take part in—the very long hair, the silly clothes, the drugs, the boring student union, the placard- bearing marches and the naive reverence for Chairman Mao and other revolutionary figures.

The pop scene after 1963 was a lyrical outpouring of an essentially feminine spirit often produced by very young people which was so powerful that even after 50 years it remains a model for rebellious youth. How fascinating that today we still listen to many of these productions without any sense of hearing old fashioned stuff, yet it is unthinkable to imagine a young Bob Dylan or John Lennon admiring music hall favourites like That Old Fashioned Mother Of Mine or Roses of Picardy, songs closer in time to the 1960s than the early Beatles are to us today!

SCULPTURE

I wouldn’t say that sculptors are in general less intelligent than other artists but clearly there is a very different sensibility at work, the quality of thought seems to be of a denser and altogether heavier texture; an activity which operates at the less poetical purple end of the artistic spectrum where it begins to slide off into the domain of the ornamental mason and master craftsman. For me there is a problem of definition as in modern times the term sculpture has been used to describe a whole range of productions: traditional sculpture built around an armature, modelling in clay, carving, what I term 3D design (as with the sticks in a pile of sand school), as well as a whole load of marginal stuff like earthworks, performance art, happenings and video which belong less to the world of aesthetics and appear to have more to do with politics and philosophy. It is now a hundred years since Duchamp signed his urinal R MUTT and I wonder just how many artistic careers have been founded on this cornerstone, the profound premise of which is that anything can be considered art if the artist says it is, the next intellectual level of attainment after realising that there is a double meaning in Animal Farm.

I have never had much contact with actual sculptors although I did get to know Alison Wilding at Wapping who is undoubtedly one of our best. I visited her studio on one occasion and had a really good talk about how she worked. I remember this as it was one of the only occasions at the Wapping studios that I ever got involved in a proper discussion about art or creativity which is surprising when you consider that in those years it was one of the largest colonies of artists this country has ever seen. Apart from meetings at those ghastly annual open studio shows I had very little to do with my fellow artists. While purporting to be socialists they mostly kept as far away as possible from the local Wapping people judging them to be largely a bunch of uneducated bigots and racists and rather than drink with them in the rough boozers patronised instead those poncy riverside tourist pubs the Town of Ramsgate and the famous Prospect of Whitby. As the 1980s progressed and one after another the old local pubs closed down the nights of drinking with other artists occurred more often but even then the conversation rarely turned to anything aesthetic or cultural. After a few drinks the talk might turn instead to politics and this would usually slip into a depressingly familiar and complacent groove. Though already enjoying comfortable bourgeois lifestyles they were almost all in varying degrees left-wing and there was a feeling that you needed to fall-in with these views if you wanted to get on, and I remember one evening during the Falklands War when the news came on the radio about the Argentine airstrikes that destroyed the Sir Galahad the pub full of artists started whooping and cheering! However it was with quite homely matters that the artists felt most comfortable, in swapping stories about how they got their Acme subsidised home in Beck Road, comparing notes on someone’s new Space studio, moaning about losing their one day teaching post at Cardiff or how they had managed to wangle yet another lucrative Arts Council grant.

My only other close contact with actual sculptors had been in my final year at Corsham when they decided to give me a sort of private painting studio in the little room which I called the boiler room but which actually was a glorified electricity cupboard full of pipes, cables and meters. The way to this depressing place led through the Sculpture School, so each day I had close contact with some of the friendly chaps who laboured there. There were no traditional materials for carving such as wood or stone but instead lots of plastic, sheet metal, fibreglass and everywhere that horrid smell of resin. I often had to make my way between great heaps of sawdust, cardboard or sand uncertain about whether these represented an art work or not. Sometimes these strange heaps would lie around unaltered for ages and then suddenly disappear. When I asked what had happened to them I was told that they were finished, had been photographed and catalogued and that it was the process that mattered and not the end result. I often had a quick chat to the students about their works and would in a very short time throw up loads of possible tangential ways that these simple creations could develop and I remember the look of slightly fearful mistrust with which they looked at me as if I was taking the piss which of course in a way I was. This brings me to the main problem with sculpture: all artists make mistakes, and I reckon that between a quarter and a third of what I have produced is of little or no value. With a painting it’s easy; you chuck it or hide it away in a cupboard, but what happens when you have invested loads of time and money in a massive sculptural project and realise half way through that it’s a pile of junk! I wonder if something like this happened in the Olympic park in Stratford with that monument to the vile sycophancy of the British Art Establishment, the hideous Arcelor Mittal Orbit?

As far as traditional sculpture is concerned it is a bleak fact that apart from the very occasional masters like Rodin, Giacometti and even Henry Moore it has been more or less downhill all the way since the Ancient Greeks. But the real mystery for me is just why would anyone now bother to engage in such a ponderous and slow process—the heavy materiality of which must preclude the use of intuition or improvisation, and worst of all to so often end up with a piece of work of no more visual interest or value than the multitude of other objects that lie all around us in the everyday world.

ARCHITECTURE

You couldn’t be growing up in Thurrock 50 years ago without being aware of modern architecture. That many of our ancient buildings were torn down and replaced by what were usually very poor developments meant that we had a terribly pessimistic view of so called progress. The understandable post war rush to ruthlessly replace poor but vibrant communities with modernist examples of poor planning and the unforeseen increase in road traffic has led to the familiar desolate and alienating feel of so many of our towns. Le Corbusier and his followers with their nutty utopian visions of how the masses ought to live are largely responsible for this. The relentless enthusiasm with which these schemes were realised and the subsequent disenchantment of the British people upon whom these places were imposed has led to a pathetic reaction in recent years where any sort of poorly designed junk is allowed to be built as long as it has a traditional front elevation and a pitched roof. The best of this I call Repro architecture and is exemplified in the Poundbury township in Dorset, certainly an improvement on a lot of new developements, especially those in a rural setting, but far from a satisfactory or honourable answer to the Modernist problem. But by no means all of our post war buildings are bad. There are good examples of high density housing which might have become the basis of a sort of national style. I am thinking of places like the newer parts of the Tachbrook estate in Pimlico which I remember being built in the 1970s. If I were an architect I would above all else enjoy the challenge of raising the level of our poorest homes. What happened to the virtues of subtlety and modesty or the concept of hidden beauty? I like the way in some old European towns you might find a wonderful house and garden concealed behind some completely inconspicuous doorway set in a crumbling wall. The type of places I really hate are the ones which are flashy or expressionistic like those copies of the Sydney Opera House or the ghastly Guggenheim in Bilbao. The Georgians knew how to keep curves to an absolute minimum to achieve the best effect and I personally think there should be a law against putting up any erection which has a larger circumference at the top than at the base.

THE NOSTALGIA OF EARLY TELEVISION

It was quite a while after starting Primary school that we acquired our first television set; before this I remember children in the playground talking about cartoons and series of which I knew nothing whatever. We were not entirely ignorant of the medium as our grandfather who lived just up the road had before the coronation of our present Queen acquired from one of our farm neighbours Granny Bugg his first set, and it was on this minute and unreliable device that one evening on a visit with my father I watched enthralled a very early broadcast of The Sky at Night with the then young Patrick Moore. It may well have been on our walk home that night that my father first drew my attention to the sky full of stars overhead, pointing out the two Bears and Orion with his belt and the conspicuous red star which he called Beetlejuice, and maybe the Milky Way or the Pleiades. In years gone by most country people knew something of the night skies and of course there was a lot less artificial light then to obscure the awe- inspiring sight. One of the very first things we learnt as youngsters was to allow our eyes at night to become accustomed to the darkness and I cannot remember any country people carrying a torch and flashing the light in your face as the idiots do today. I am afraid that even good habits and customs go out of use—we always took a walking stick on a ramble or plucked some piece of ash or elm from the hedge, but now the tracks and field paths remain overgrown. We also learnt a little about the most common trees, bushes and flowers something about wild animals and birds and the rudiments of weather lore.

The science of Television had not in those days reached anywhere near the levels of perfection we enjoy now and rarely a week went by without a problem with the transmission of a programme with the frustrating wait that ensued while one was left anxiously staring at the test card. More often than not the problem was with the actual set or the aerial. We all became adept at knowing which knobs needed adjusting and we seemed to have most trouble with things called Vertical Hold and Horizontal Hold which were meant to stop the picture from sliding up and down and across but which had an infuriating tendency after prolonged and seemingly successful twiddling to go wrong again as soon as you sat back to enjoy the rest of the programme. We would then resort to tapping and banging the top of the set which worked surprisingly often. If these manoeuvres were unsuccessful my father (and only he was allowed to do this) would unscrew the board at the back and go to work usually in a pretty hot temper on the complex of valves, knobs and wires inside. If his efforts failed a walk up to the village phone box ensued from where he would telephone Mr Rayner who had a TV repair shop in New Road in Grays. This was in the upper part of town near the church and close by was that other important place in our childhood the establishment of Frank West Gentlemen’s outfitters. I remember many unhappy Saturday afternoon visits to that shop for fittings of new clothes which I always felt to be such a detestable waste of time, and it is a fact that much of the clothing in those days was made of harsh, itchy and scratchy material and was so often ill- fitting. However one fascinating thing these premises still possessed up until the early 1960s was a strange contraption by means of which monies were whizzed around the store by wires above our heads on a sort of miniature monorail system from every department to a central cashier who was housed in a secure little wooden compartment. How I used to dread those shopping afternoons with the usual visits to Marks and Spencer’s, the huge Co Op and old fashioned and crowded Woollies with its high counters, narrow aisles and wooden parquet flooring where on one terrifying occasion I somehow became separated from my parents!

As a family we watched all the usual programmes; some cartoons and then the evening news and on dark nights when we didn’t go out maybe a favourite cowboy series, a game show or comedy; we even enjoyed the advertisements on ITV especially the enchanting Christmas ones. As up until the mid-sixties there were only two channels and it was unthinkable that a home would have more than one TV set, it meant that the entire country watched more or less the same things. There were a few broadcasts like that early Sky at Night which affected me in an unusual and unforgettable way. Because my father worked eight hour shifts and my mother would somehow manage to remain busy at housework until late, my brother and I would often be left alone to watch telly together on a winter’s evening when the wind would come roaring and booming up from the marshes and it was on one of these occasions that I remember being fascinated (subtitles and all) by De Sica’s famous film Bicycle Thieves. Another time with lights off we saw one of those really very frightening early Quatermass films, and I was even more scared seeing Charles Laughton as the Hunchback of Norte Dame. I can’t remember my grandmother having television on during the daytime unless it was to watch sport, so I have no idea why one wet Sunday afternoon they had on the 1939 film of Wuthering Heights with Lawrence Olivier which affected me deeply and which I still think is one of the best cinematic interpretations of a really great book. It was probably about the same time that during ‘tea’ one Saturday, for we always had supper at their cottage at weekends, that after the football results the very first episode of Doctor Who came on. My parents always sat at the table in the tiny room with their backs to the television but it wasn’t long before my father had heard enough and said through gritted teeth ‘what a bloody load of crap—shut it off’ and prophesying that it would be taken off by Christmas. The unique music, wonky looking sets, the grainy black and white film and the not always convincing but nevertheless frightening aliens gave to those early episodes a sort of sinister fascination which was completely lost later on. Most importantly the first Doctor, William Hartnell, with his long silver hair played the part amidst even the ridiculous or absurd with the utmost gravity. He never resorted to clowning or buffoonery (as all subsequent Doctors did), and I suppose he unwittingly fulfilled the Jungian archetype of the Wise Old Man which helped to make those early episodes of the long running series such compulsive viewing.

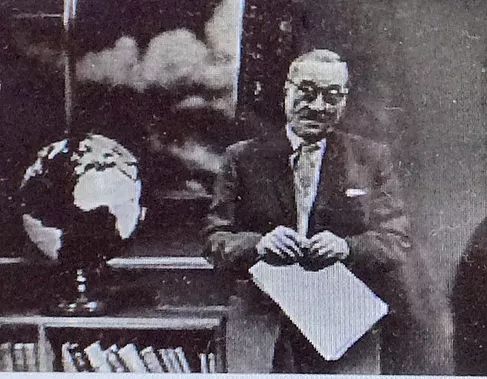

The legendary filmmaker John Grierson used to have an early evening programme from Scottish television called This Wonderful World which showed clever and often abstract animated films and short documentaries from around the world which we loved watching. But it was the ending of this show which always had a profound effect on me as if a mysterious doorway had opened onto another world! A stern looking Grierson would be at his desk on top of which among other paraphernalia was a large globe while behind what was clearly a fake window great evening clouds were rolling up rather as if the studio was set high up on a headland facing the Atlantic blasts. For some reason I always seemed to derive a strange and unforgettable thrill when against this backdrop the great man delivered his usual farewell: “to those in the Highlands and the Lowlands and those over the Border I wish you all a very goodnight’.